- Home

- Fiona Hodgkin

The Tennis Player from Bermuda Page 3

The Tennis Player from Bermuda Read online

Page 3

I wanted everyone there to remember this match forever.

It was a hot Bermuda day, but I felt so cold my hands were shaking between points. I fired volleys to her forehand just to show that I could catch her shot with my racket, drain the ball’s terrific kinetic energy with my hand and forearm, and then sharply angle my volley softly into her service box for a clear winner.

I served ace after ace and volleyed winner after winner; I took service game after service game at love. I hit only for the outer edges of the lines; I took ferocious, insane chances and came out on top each time. In the second set, I started following in my return of her first serve to volley winners.

I wanted to crush her, and I wanted everyone in Bermuda to watch me do it. She fought back; she would never give up; but I overwhelmed her.

Ahead 4-love in the second set, I lunged to volley one of her shots, got too far out over my feet, fell, hit the court, and lacerated the distal surface of my left elbow. I was bleeding, and suddenly there was blood all over the side of my tennis dress. I walked to the sideline and found a towel to stanch the blood. I looked up and saw Father starting down the steps of the bleachers toward the court.

“No, Father. Stay where you are,” I called loudly.

The chair umpire, George Michaels, said from the chair, “Miss Hodgkin, perhaps Doctor Hodgkin or Doctor Wilson should look at your arm before you resume play.” My mother used her maiden name, Wilson, in her medical practice – which was practically a scandal in those days.

“Mr Michaels, I am ready to play now.” I picked up my racket and walked back to the baseline. Mrs Martin, across the net, was expressionless.

It was over in 34 minutes. 6-1, 6-0.

I walked to the net, shook hands with Mrs Martin, and went to pick up a towel to hold to my elbow. Mrs Martin said nothing to me. The spectators, even my parents, were silent. There was no applause. I didn’t care. I knew the spectators thought I hadn’t been sporting.

It was one thing to win a match handily. That would be acceptable. It was quite another for a young girl like me to appear to dominate an older, respected player. That was Not Done. To make it even worse, I had played with an obvious grim fury. I knew Mother and Father would disapprove.

But I had won; I was the champion; that was all I cared about.

Mr Michaels fussily arranged a small table on the court with the two cheap pewter plates that were the prizes for the finalist and the champion. Mrs Martin and I stood side by side. I was still holding a towel to my elbow. Mrs Martin walked forward and brushed past Mr Michaels, who was attempting to award her the finalist plate. Instead, she walked to the center of the court, folded her arms over her chest, and looked out at the spectators.

Everyone in the stadium, still silent, stood up together at once. In Bermuda, in those days, this was a mark of immense respect.

As a teenager – back then she was ‘Miss Rachel Outerbridge’ – she had sailed on a steamship to Australia by herself. She was determined to become an unbeatable tennis machine, but she had almost no money. During her first week in Melbourne, she lived, homesick and lonely, in a decrepit rooming house in St. Kilda, ate only cheap Greek bread, drank tap water, and rode the No. 16 tram down Glenferries Road to Kooyong.

But when she played in the second round of the Australian championship on the lawns at Kooyong, Nell Hopman watched. Nell had just won her own second round match. Nell turned to her husband. “Who is that girl? What’s that flag on her dress?”

That afternoon, Nell and Harry found a wealthy family in the Toorak neighborhood to take in Rachel. For her first two days with that family, Rachel told me decades later, all she had done was eat.

And Nell, being Nell, had taken Rachel’s pocketbook without asking, rummaged around in it and – just as Nell expected – found no money. So she had the Lawn Tennis Association of Victoria give Rachel some spending money. This is what Rachel told me she remembered most: that the LTAV had given her money for her pocketbook.

Rachel was the youngest Australian ladies’ singles champion until Margaret Smith, two decades later. An old black and white photograph of Rachel, taken just after she defeated Nell in the final, shows a shy young girl clutching her racket to her chest. The framed photo still hangs in the members’ bar in the Kooyong clubhouse.

The news that Rachel had won the championship at Kooyong flashed to Bermuda in the middle of the night, and the next morning all Bermuda was on Front Street, cheering. Her anxious parents sent her a telegram congratulating her but urging her to come home to Bermuda.

She could afford to send only a one-word telegram in reply: WIMBLEDON.

I thought, ‘What would she have done for Bermuda in tennis if the war hadn’t come?’ I think everyone else there that day had the same thought.

Mrs Martin turned away from the spectators, and Mr Michaels, relieved that she was finally going to accept her finalist plate, picked it up from the table.

“George, will you kindly forget those silly plates?”

She walked back to where I was standing. I tensed, expecting she might slap me across the face. Instead, she gently put her arm around my shoulders and walked with me back onto the court. I stood there with my hand holding the towel against my left elbow, with bloodstains on my dress, and Mrs Martin’s arm around me. The crowd was completely silent.

Mrs Martin was at least four inches taller than I. She leaned her head down and kissed my cheek.

Then she said, loudly enough for everyone to hear, “Miss Hodgkin, that match was quite well played. Bermuda should be proud of you. I am.”

The whole stadium suddenly exploded with cheers. My parents forgot themselves to such an extent that they actually hugged one another in public and began yelling together, “Fiona! Fiona!” Everyone took up crying out my name.

Mrs Martin turned to me and said quietly, “Now we need to ask one of your parents to look after your arm.”

SEPTEMBER 1961

PAGET PARISH

BERMUDA

From today’s perspective, my application to enter Smith College appears ridiculously simple. It consisted of a brief letter in late 1960 from Mother to Thomas Mendenhall, the then President of Smith, noting that I, Miss Fiona Alice Ashburton Hodgkin, of Paget, Bermuda, would be 18 years of age on July 1, 1961; that I was the granddaughter of Fiona Alice Wilson, née Ashburton, M.D., Smith class of 1912; that I was the daughter of herself, Fiona Alice Ashburton Hodgkin, née Wilson, M.D., Smith class of 1935; and that I would appreciate the opportunity to matriculate at Smith in the fall of 1961.

Mother, perhaps unnecessarily, added that I would pursue a pre-medical course of study at Smith.

Professor Mendenhall replied in an equally short letter to Mother stating merely that I would room in Emerson House (where Mother had lived), that classes would begin on Tuesday, September 5, 1961, and finally, that Mother would receive the college’s statement for my fees and tuition.

And that was that.

Bermuda families, even today, are frugal. We are so isolated, and much more so then than now. I was not surprised when Mother, who was helping me pack for Smith, lugged out storage boxes of her own winter clothes from Smith for me to take to Northampton. The clothes were outlandish and hideous. The winter boots were enormous, the sweaters incredibly thick; I could not imagine what it would be like to wear them. I had never seen snow except in cinemas and photographs. I did know what snow was: it was white and cold.

The day before I left Bermuda to fly to New York on my way to Smith, I went to see Mrs Martin. She was hanging her family’s laundry to dry on a line in their garden. She saw me getting off my bicycle, and she put down the laundry and waited for me to walk through the garden to where she was standing.

“I leave tomorrow. I came to say goodbye – and to thank you.”

“I appreciate you coming to see me.”

She didn’t say anything more. I waited and finally said, “Could we sit down?”

We sat down on the grass. She to

ok my hand and held it. I was happy just sitting with her.

After a minute, she said, “You play at a level that, in a few years, will give you a place in international competition.”

“You did as well.”

“A long time ago.”

“I want to do as well as I can at tennis.”

“You want to win Wimbledon.”

She was exactly right. “I can’t expect it to happen for me.”

She snorted. “We spent years on tennis courts so you could predict you can’t win?”

“You didn’t win.”

“I didn’t. I wanted to.”

“But the weather was terrible, and you were all alone in England.”

“I wasn’t alone. I was with a young man. A German tennis player from Berlin.” She hesitated. “I met him at Kooyong.”

“You were seeing him?”

“Well, ‘seeing him’ is the polite way of saying what I was doing. The evening before I played Alice, he broke up with me. I never saw him again.”

She stopped. I thought this was all she would say, but then she started again: “Later, I heard we shot down his bomber over the Channel in the Battle of Britain. He drowned.”

She paused for a long time. “Or so I heard.”

“Why did he break up with you?” I couldn’t help asking, but I had crossed a line. This man broke up with her the evening before her Wimbledon final? I was dumbfounded.

“It made no difference. My match with Alice would have turned out the same anyway.”

“How can you know that?”

She didn’t answer. She leaned over, put her arm around me, and pulled my head against her chest, with her hand holding my head to her.

She held me for a few moments. “It’s tomorrow, then?”

“Yes.”

She stood and brushed off her skirt. She didn’t say goodbye. She turned and went back to her laundry, and I took my bicycle and went home.

SEPTEMBER 1961

SMITH COLLEGE

NORTHAMPTON, MASSACHUSETTS

I loved Smith, but I had never been away from my parents before. Although they went home to England on holiday every three or four years, they always took me along. I say they went ‘home’ to England because that’s what they would say, but both of them were born in Bermuda. Both of my grandfathers were born in Bermuda as well. And Mother’s mother was an American. As a child, I began calling her ‘American Grandmother.’ Only Father’s mother had been born in England. Naturally, I called her ‘English Grandmother.’

I was terribly homesick for Bermuda.

In the 1880s, Smith had been one of the first American colleges to have a tennis team, and tennis had been a fad among Smith students. The Upper Campus had been covered with grass courts with narrow strips of fabric for the lines, which were held down to the grass by – what else? – hairpins.

The first day of practice for the Smith tennis team was several days after classes began in September. I was a few minutes late to practice because my chemistry laboratory ran long, and when I got to the courts, about eight young ladies, from first years to seniors, were already running in a circle on one side of the court while a young man standing on the opposite service line – the team’s coach, I learned – was feeding them balls from a large basket. He must have told the girls to hit the balls deep, because they didn’t seem to be hitting the balls back to him. Instead, they were spraying the balls all over the court.

The coach kept calling out, “Good! Good shot! Keep at it!”

This was a different approach to tennis than that employed by Mrs Martin.

He caught sight of me in my tennis dress, waved his arm, and yelled, “Hi! Come join in!”

I dutifully inserted myself into the circle of girls. But when my turn came, the coach accidentally fed me a ball that nicked the net cord and then dropped softly into my side of the court close to the net. It bounced up only 10 centimeters or so.

I was already there. Both my right knee and the lower rim of my racket grazed the court surface as I half-volleyed the ball. I didn’t try to do anything with it; I just flicked it over the net to the coach.

He looked at me for a moment, and then I returned to the circle of girls.

On my next turn, he hit the ball straight to me. I took two small steps back, swung my shoulders around so I was perpendicular to the net, took my racket back low, and hit the ball with heavy topspin. It flew a meter over the net but then fell sharply and just touched the baseline. I had hit the ball so hard that it drove itself halfway through one of the gaps in the chain-link fence at the back of the court.

The coach held up his hand to stop the circle of girls. “Can you do that again?”

“I think so.”

The coach hit me a hard backhand, with a bit of backspin so that the ball, he thought, would bounce up at steeper angle than I expected. But I didn’t bother letting it bounce. Instead, I closed in and volleyed his shot. I let my forearm recoil to drain most of the pace from the ball, which popped back over the net and landed at his feet.

The coach hit back a high, deep overhead.

I drifted back, used my left index finger to fix the ball as it fell back toward the court, and hit an overhead back to him.

He popped the ball up again, and I adjusted my position, set up, and again just hit the ball back to him.

This time he lobbed the ball high and to my backhand. I had to turn around so that I was facing my own baseline. I looked up at the ball, jumped, and swung over my shoulder. The ball landed at his feet.

The coach and I were both laughing. My Smith teammates were standing beside the court with their mouths open.

He hit another overhead high into the air over the court. Still laughing, I made a show of bouncing from one foot to the other as though I were trying to decide which direction to smash the ball. Finally, while the ball was still on its trajectory over the court, I pointed with my left hand and yelled, “Your ad court!”

I let the ball bounce. It went well above my head. I smashed it. The coach had moved to his ad court and, though he lunged, the ball whipped past him. It barely nicked the outside of his ad court baseline.

He looked back at the fence. Now there were two balls stuck in it. The coach motioned for me to meet him at the net. “Are you an amateur? You can’t play on the Smith team if you’re a professional.”

“I’m an amateur.”

“I’ve never seen you before. You must be starting your first year.”

“Yes.”

“What’s your name?”

“Fiona Hodgkin.”

“Well, Fiona, you’re playing in the number one position on the team. Come over to this side of the net and feed balls to your teammates. I’ll move over there and help them with their ground strokes.”

A minute later, I was standing beside the basket of balls and feeding them to my teammates. I was yelling, “Bend your knees! Good shot! Drop the racket head! Let’s go, Smithies!”

MARCH 1962

SPRING HOLIDAY FROM SMITH

PAGET PARISH, BERMUDA

Smith kindly rearranged my classes to give me a full two weeks of spring holiday, and I took an airplane home from New York’s Idlewild Airport. When I landed at Kindley Field, my parents were waiting for me; I was thrilled to see them. We took a taxi from the airport, and so I was quickly at Midpoint and back in my own room.

The next morning, I met Mrs Martin at Coral Beach for a tennis match. We embraced, and I said, “I missed you so much.”

She said, “Let’s knock up.”

“Yes, but first I have to tell you about all the different drills we do in tennis practice; they’re quite humorous.” I said this just to hear her reaction.

She snorted. “After our match perhaps.”

But it was wonderful to see her and to play against her again.

On my second evening at home, I was having tea with my parents, when Mother said that she had spoken that day by telephone with Mrs Pemberton in Tucker

’s Town, who said that her nephew, Mark Thakeham, was visiting from England for the school holiday.

“She’s putting together a mixed doubles party for young people tomorrow afternoon, and she wanted to know if you could come join them.”

Mrs Pemberton’s home was called ‘Tempest,’ and it had a private grass tennis court, one of only two in Bermuda, at least to my knowledge. In the past several years, Mrs Pemberton had invited me to play there four or five times, and I had always accepted, just to have the experience of playing on grass. It is difficult, even if one is wealthy, to have a grass tennis court in Bermuda. Our climate is not well suited for it. Tennis players look at the beautiful greens on our golf courses and think, “This is the perfect place for a lawn tennis court.”

The golf greens, though, support a few people each day who walk, slowly, across them to hit, gently, a small ball that rolls softly on the grass.

A tennis court has to put up with someone like me dragging a toe across the same foot of grass probably 80 times in a single match and then pounding along exactly the same path each time toward the net. Even in England, with consistently cool temperatures and plenty of rain, and as small as I am, I can damage a grass court in a single match.

In Bermuda? With inconsistent rainfall and hot temperatures? A grass court doesn’t work well.

But, for all that, the grass court at Tempest was perfect and beautiful, probably because it was rarely played upon. It was for display, not tennis. Mrs Pemberton was not Bermudian, and she did not live in Bermuda. She was from England and stayed at Tempest only on holiday.

Father spoke up. “I served with Ralph Thakeham in the war. First-rate physician. First-rate officer, for that. Now a well-known senior medical consultant in London. He’s ‘Viscount Thakeham,’ of course, but Ralph never uses the title. His patients call him just ‘Doctor Thakeham.’ He’s the younger brother of our Mrs Pemberton in Tucker’s Town. I hear good things about the young Mark Thakeham. He’s fourth year medicine at Cambridge, and he played tennis for Cambridge.”

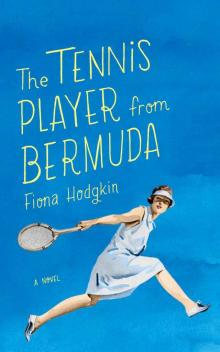

The Tennis Player from Bermuda

The Tennis Player from Bermuda